13 March 2018

|

Cornish mineworkers, and often their families too, were to travel to destinations all over the world in search of work through the 1800s and early 1900s. Ainsley Cocks, of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site, looks particularly at the families who moved from Cornwall to Cumbria

In 2016 the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site celebrated its ‘Tinth’ (tenth) anniversary, with Golden Tree Productions’ ‘Man Engine’ - an 11 metre high mechanical puppet - creating quite a stir as the centre piece. As the Man Engine is about to embark on its much anticipated 2018 Resurrection Tour, the World Heritage Site Office has commissioned a programme of genealogical research to add detail to what is known of mineworkers from Cornwall and their travels to live and work elsewhere in the UK. Ainsley Cocks, of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site, writes about the discoveries made...

Mining in Cornwall & Devon

The 18th and 19th centuries saw an explosion of metal mining take place within Cornwall and neighbouring Devon, through the exploitation of the Cornubian Orefield for predominantly copper and tin. Production of these two key non-ferrous metals helped progress and sustain Britain’s Industrial Revolution and has bequeathed a unique landscape legacy. This cultural inheritance was recognised as being internationally important in 2006, with the designation by UNESCO of World Heritage Site status for the mining districts of Cornwall and west Devon.

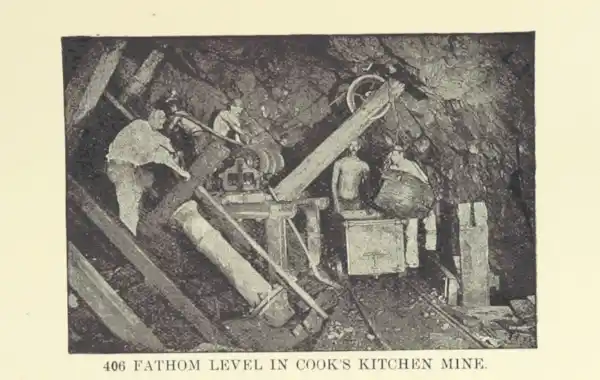

Described as being probably the most important mining district in the world by the mid-1800s, Cornwall particularly had become a magnet for all those concerned with efficient metalliferous mining and steam pumping, the latter essential to unwater deep mines. Indeed, so proficient had Cornish industry become in the art and science of large volume steam pumping that by the 1870s it has been estimated 70 per cent of all London’s water supply was being pumped by Harvey’s engines, constructed at their foundry in Hayle. Cornwall had thus established an industrial ‘Silicon Valley’ of sorts around steam technology, with its latest high-pressure designs being at the leading edge of what was then considered theoretically possible.

Cornish mining migration

With the international mining and engineering spotlight shone directly on Cornwall it is unsurprising that its mineworkers and technology became much sought after, wherever a new mining venture was being commenced or where existing mine workings were being overhauled. This prompted a wave of mining related migration which was to grow to encompass all the inhabitable continents by the close of the 19th century. Cornish mineworkers, and often their families too, were to travel to destinations as far afield as Australia and New Zealand, North, Central and South America, and South Africa, along with many destinations across continental Europe. During the century from 1815 to the start of the First World War, it has been estimated that around 250,000-500,000 people migrated from Cornwall with more than half of these thought to have migrated to other areas in the UK. While considerable emphasis has been given by academics and other researchers to overseas migrant destinations hitherto, relatively little has been published on the nature and impacts of Cornish mineworkers relocating within Britain.

Roose: a Cornish migrant destination

Perhaps the single destination which may best exemplify the Cornish mining migration process within the UK is the village of Roose in Barrow-in-Furness (now within Cumbria, formerly Lancashire), where hundreds of Cornish mineworkers chose to settle after 1873. While an influx for iron mining is understood to have already taken place by the 1860s, it was the discovery of what would become the Stank Mines in 1871 that prompted the construction of extensive company housing for the required workforce. Here two rows of 196 terraced cottages were built by the Barrow Haematite Steel Company and almost exclusively occupied by the Cornish, using their hard rock mining skills to work the locally rich haematite ore. The newly created settlement was to have its own school, mission church and Sunday school, with the church - it is understood - being named St Perrans, after the Cornish Saint, to attract Cornish patronage.

Considering the iron mining districts of what were then the counties of Cumberland and Lancashire more widely, a study recently undertaken by genealogist Stephen Colwill, indicates that in excess of 3,500 Cornish-born were living across eight neighbouring parishes by 1881. These include Millom, Egremont, and Cleator, in addition to Barrow-in-Furness. Fortunately surnames occurring in Cornwall in the 19th century are, then as now, sufficiently distinctive to the experienced researcher to enable their ready identification within census returns. Such an analysis has revealed the occupants of both North and South Rows in Roose as being predominantly Cornish. The research, commissioned by the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site, has also highlighted one such distinctively named Cornish mining family - the Trescatherics - that lived within North Row.

Research indicates the Trescatherics’ connection with Roose starts with John Trescothick, who was born in Illogan, Cornwall, in 1854, and Elizabeth (née Roberts), born at Ludgvan, Cornwall, around 1885. A few years earlier, in 1871, John Trescothick, then aged 17, is recorded as living with his parents at the hamlet of Bridge, Illogan, where he was employed as a ‘Tin Stamps Boy’ - tending the ore crushing stamps at a local mine. John was, himself, from mining stock, with his father William Trescothick (Trescowthick) recorded as a ‘Tin Miner’ born at Illogan around 1810. One of John and Elizabeth’s sons, Thomas Henry Trescatheric, was born in Roose in 1882, a few years after his parents arrived from Cornwall. John and Elizabeth are understood to have been some of the earliest residents of North Row and are recorded in the 1881 Census as living at number 33.

While the Trescothicks and many others were to benefit significantly from the much-needed employment provided by the iron mines, this was ultimately to turn out to be not entirely consistent or especially long-lasting. It is understood a short but significant decline in the fortunes of the iron producers during the later 1870s prompted many to depart their homes for new mining settlements in North America, with Bisbee, Arizona, being a favoured destination with an already established Cornish enclave. The iron mines at Barrow continued as major employers until the early years of the 20th century, at which point these finally closed. The Trescothicks are understood to have stayed in their Roose home, however, as they are recorded at the same address, under the name Trescatheric, 30 years later in 1911.

Fortunately many of the Cornish were able to secure alternative employment following the demise of the Stank Mines, within the nearby naval construction and armaments works of Vickers, Sons and Maxim, Ltd. Here, the experience of the Cornish as mineworkers using compressed air rock drills proved invaluable where skilled air riveters - known locally as ‘windyjacks’ - were in considerable demand along with metal fabricators and machinists.

Today the village of Roose looks essentially much as it did in the 1870s when first built, with its distinctive terraced cottages along North and South Rows located just to the east, and almost at odds with, its larger neighbour Barrow-in-Furness. But how many know today of the presence of the Cornish here from the late 1800s and their distinctive contribution to the prosperity of Barrow?

.jpg)