13 March 2015

|

Ask anyone to name a famous document from history and Magna Carta has got to top the bill. So I went along to the preview on Wedn

Ask anyone to name a famous document from history and Magna Carta has got to top the bill. So I went along to the preview on Wednesday, to the British Library exhibition that opens today, expecting a homage to Magna Carta - which the exhibition was, with me as the pilgrim, which I was - but the experience was so many other things too it knocked my socks off and I left buzzing and sated on a feast of history.

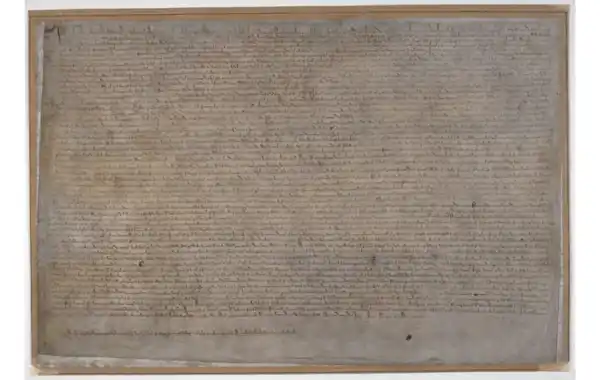

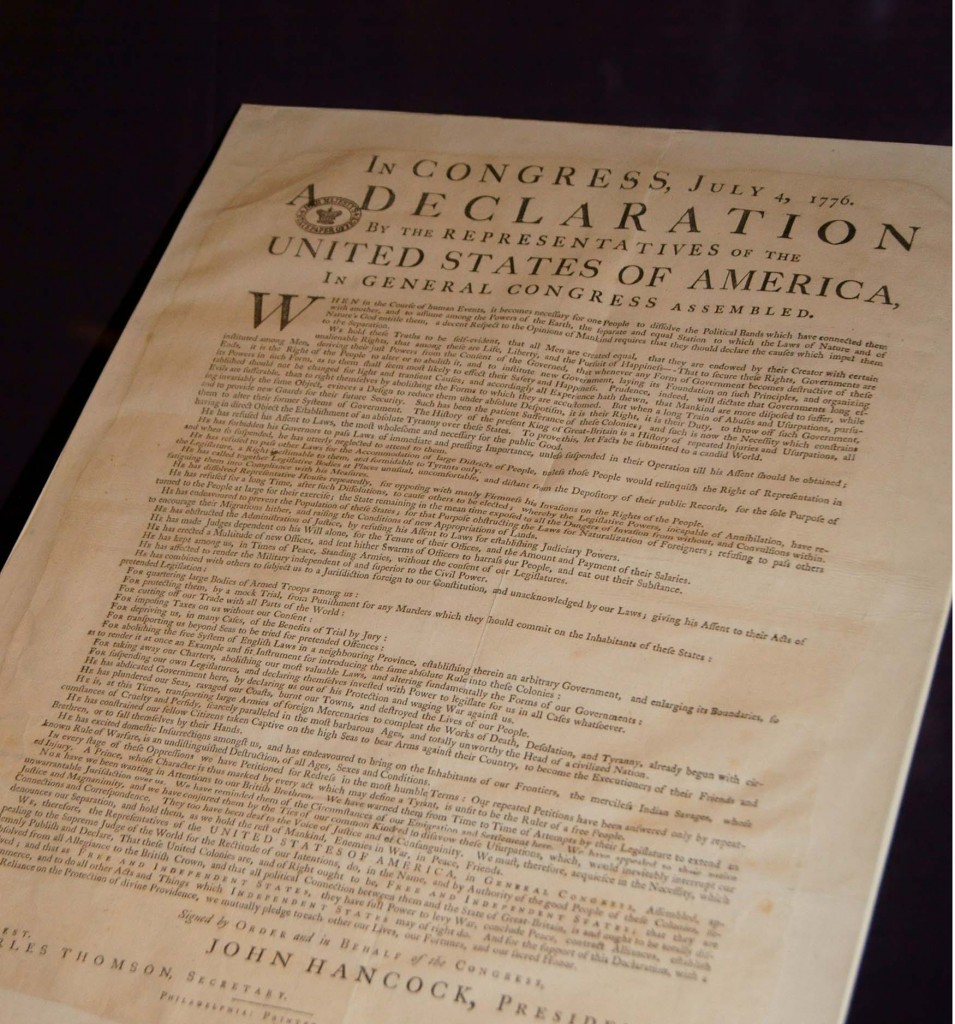

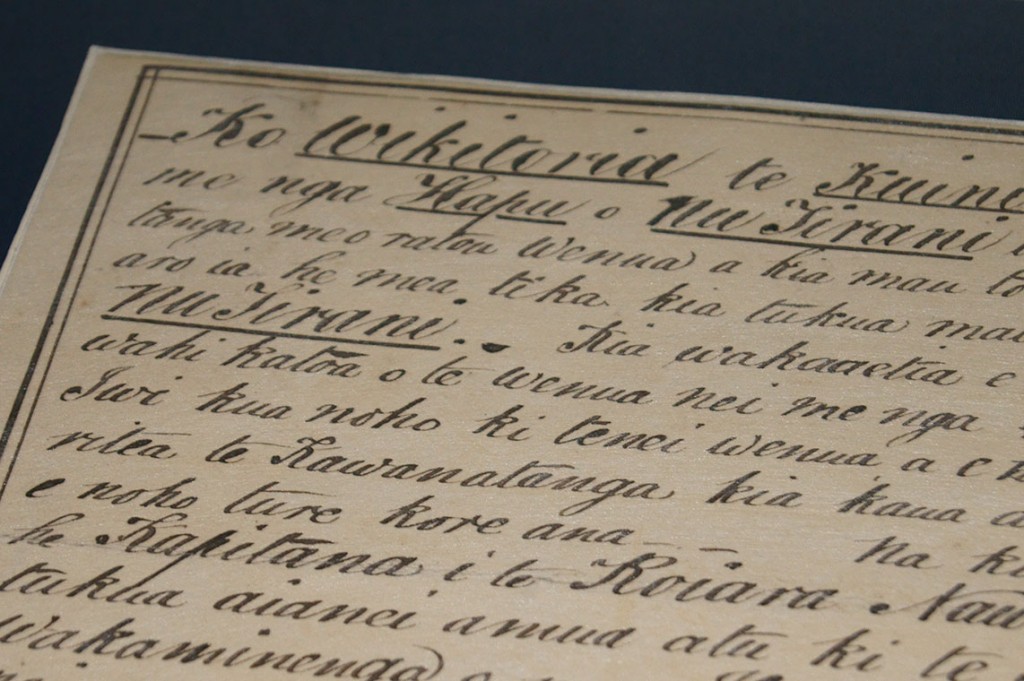

Each of the 200-plus items on display is an ‘A-lister’ historical document in its own right: the Bill of Rights uncompromisingly presented to William and Mary in 1689, copies the American Declaration of Independence (including the handwritten draft by Thomas Jefferson, interestingly including a suggestion that slavery be abolished), the Treaty of Waitangi concerning Maori rights and land ownership from 1840, and of course several versions (from 1215 through to 1297) of Magna Carta itself - as it inched its way towards the Statute Book. And yes - this exhibition being the awesome collection that it is - the Statute Book itself is there too.

And this is the thing that I really relished - in one exhibition the curatorial teams have brought together, and brought to life, so many of the key historical documents that we hear referred to time and again, from school kids onwards. These treaties, bills and charters that we learn about as children aren’t just stuffy old words; they are the result of people pitting their wits, and wrestling with problems about how countries are run, people governed and power is allocated.

One of the exhibits near the entrance is a display of rather scruffy-looking wooden sticks. Curious I took a peek and it turns out these were the barons’ tally sticks dating just a few decades before Magna Carta. Forgive my ignorance, everyone who knows what they are, but I was intrigued. A tally stick was effectively a twig, split from top to bottom, with notches scratched on the side. Each time a baron paid his taxes to the king, he presented this half of the stick, to be matched with the king’s half (to see that they tallied), and duly notched, by way of proof of payment - and therefore loyalty. And these sticks, to me, speak volumes about the society that they came from. It’s fascinating to see how our ancestors grappled with the concepts of power, rights, rule and justice. And it’s interesting to see the context that led up to Magna Carta, and yet more fascinating to see the events that followed: from Thomas More citing it in his defence, prior to his execution in 1536 (More’s publication is on display); to a mention of Magna Carta in a recording of Nelson Mandela’s speech at the Rivonia Trial in 1964. Something about Magna Carta has struck a chord that has continued to sound through the centuries.

But what of the document itself? The final item on display in the exhibition is the British Library’s ‘good copy’ of Magna Carta from 1215 (as opposed to the fire damaged one, complete with melted seal). The good copy is an unprepossessing looking piece of parchment, roughly A3 size, with no elaborate drop cap nor illuminated letter to start, and no flourishing signatures to end it. It’s crammed from top to bottom, side to side (no margins) in tiny medieval Latin. But even though I can’t, I’m ashamed to say, read a word of it, it looks to me like a document that clearly means business.

Make sure you visit!

The Magna Carta exhibition at the British Library runs until 1 September 2015.

Tickets can be bought from [email protected] (01937 546546).

And to find out more visit www.bl.uk/magna-carta.

This is a printed version of the Declaration of Independence, created within hours of the handwritten version being ratified. Constrast this with the first printed version of Magna Carta, which couldn’t happen for three centuries, such is progress. © Helen Tovey.

Often referred to as the Maori Magna Carta, the Treaty of Waitangi tried to clarify land rights in New Zealand in 1840. © Helen Tovey.

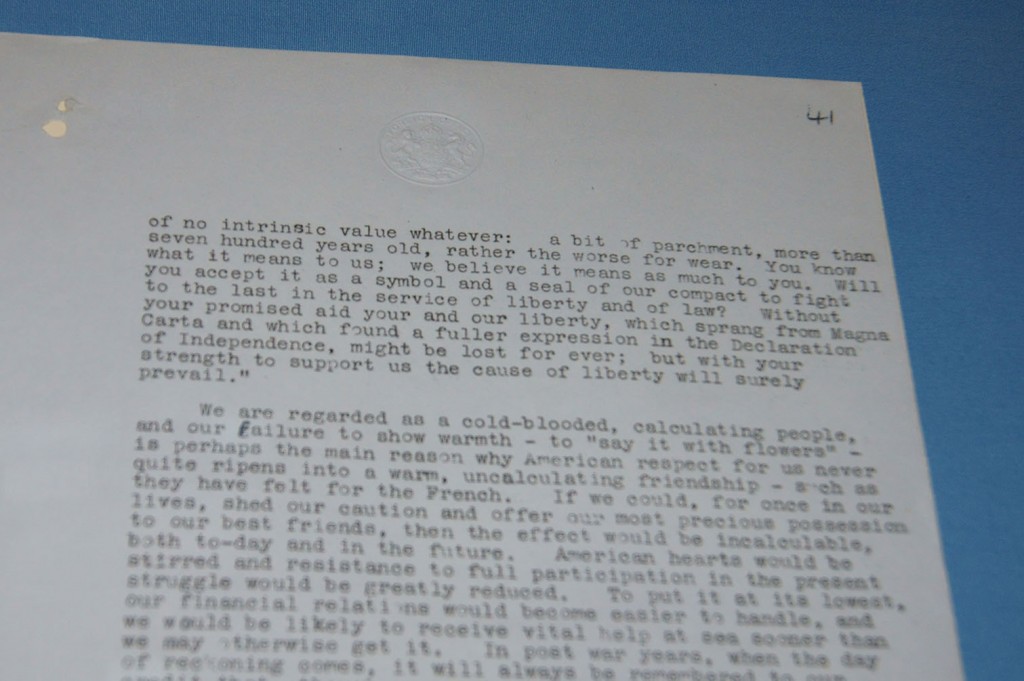

In this correspondence from 1941 the Foreign Office describes the Magna Carta as being of ‘no intrinsic value whatever’. However, the idea was still being mooted to donate Lincoln’s copy of Magna Carta to the Americans by way of a thank you for their support in the war effort. © Helen Tovey

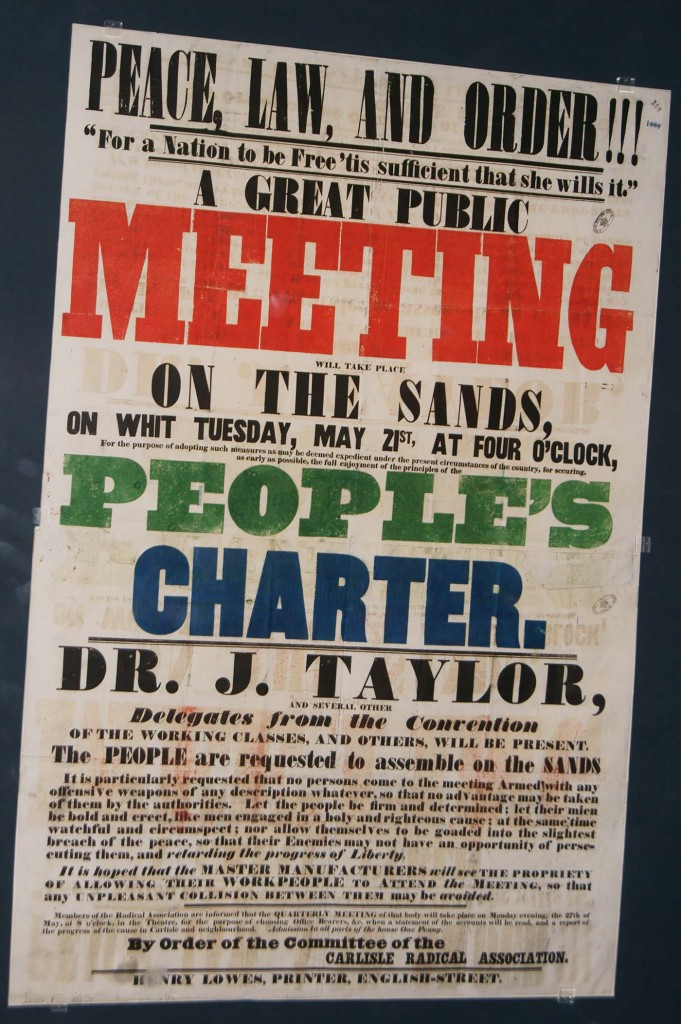

A Chartist rally poster, used by our Victorian ancestors in their campaign. © Helen Tovey.