05 January 2017

|

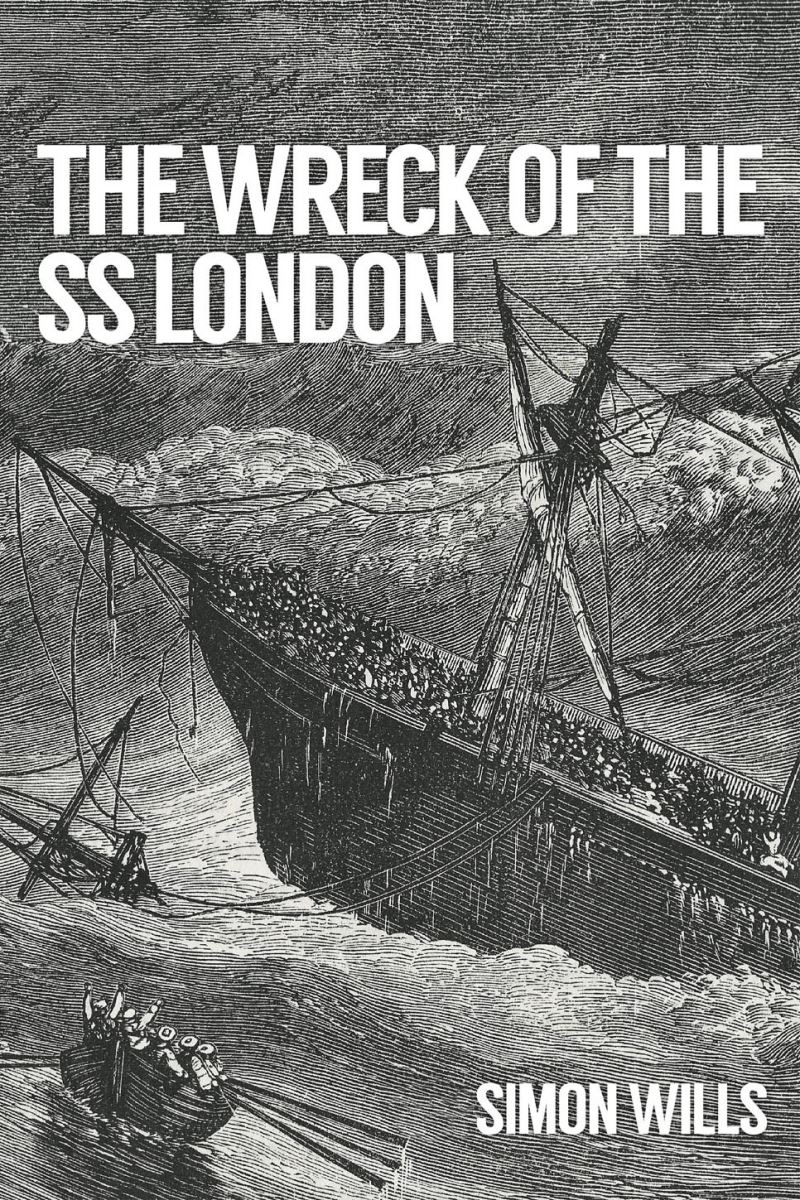

Maritime genealogist Simon Wills examines the aftermath of the SS London shipwreck of 1866 to discover how attitudes to tragedy have changed over the years.

Maritime genealogist Simon Wills examines the aftermath of the SS London shipwreck of 1866 to discover how attitudes to tragedy have changed over the years. Discover more about Victorian ancestors in our Victorian special, available from our website.

I’ve just written a book about a once-famous shipwreck. The SS London was a luxury liner that sank in the Bay of Biscay on 11 January 1866 taking 243 people to a watery grave, and only three passengers (pictured below) survived to tell the tale. It was a notorious nineteenth century disaster and it’s interesting to compare how the Victorians responded to this kind of event, compared to us in the 21st century.

However, there were differences. For one thing, it took six days for the story to break, even though the ship was lost close to home, because it took that long for the survivors to get back. And the story wasn’t broken by some enormous media empire with a far-reaching net of reporters, but a regional newspaper called the Western Times because the survivors came ashore at Plymouth. It was thought best to spare readers the ‘gory details’ of how people died so this tended to be glossed over.

However, there were differences. For one thing, it took six days for the story to break, even though the ship was lost close to home, because it took that long for the survivors to get back. And the story wasn’t broken by some enormous media empire with a far-reaching net of reporters, but a regional newspaper called the Western Times because the survivors came ashore at Plymouth. It was thought best to spare readers the ‘gory details’ of how people died so this tended to be glossed over.Follow us on facebook

Follow us on twitter

Sign up for our free e-newsletter

Discover Family Tree magazine

The situation was worse in Australia, where many of the passengers haled from, or were bound. In the days before modern communications, relatives and friends of the dead in Australia continued to live in blissful ignorance of the disaster for over two months before the news could be brought to them by ship.

RUMOUR AND SCANDAL

There was scandal attached to the calamity too. There was so much speculation that Gustavus Vaughan Brooke the actor, who drowned in the wreck, had eloped with another woman that his wife wrote to The Times to scotch the rumours. One poor woman felt so guilty that she’d advised her late sister to board the SS London that she committed suicide. And then there was the public inquiry into the tragedy, which the press enjoyed labelling as a farce (which it was), and pointing the finger at dodgy politicians, crooked ship-owners, and inept ship’s officers.

However, in other ways the Victorians approached the news of a national disaster quite differently to us. For one thing, there was little intrusive coverage in the press about the grief of bereaved individuals. There were also no photographs in the papers of course, but some included sketches of the sinking ship or of key persons involved.

At this time, ballads were still sung to convey news, and printed ballad sheets were sold to be sung in public. You can read an example about the SS London from the Bodleian Library collection, and also listen to folksinger Gavin Atkin singing one of the ballads. People wanted to mark the passing of important events, and poetry was another popular way to do this.

.jpg) Victorian poets flocked to the SS London disaster like moths to a candle. Many poems were written and published, and most of them were terrible. The worst were undoubtedly the verses penned by William McGonagall, a man considered Britain’s worst ever poet. He was so awful that people threw things at him when he gave public recitals.

Victorian poets flocked to the SS London disaster like moths to a candle. Many poems were written and published, and most of them were terrible. The worst were undoubtedly the verses penned by William McGonagall, a man considered Britain’s worst ever poet. He was so awful that people threw things at him when he gave public recitals.

The Church had a significant role when it came to national mourning, and sermons were an important salve to the nation’s wound. Leading clergy also wrote to newspapers and issued publications about the tragedy to console people and ensure that their faith was not shaken.

These days we would think it very bad taste to issue commemorative china or a set of postcards to mark a catastrophe, but to the Victorians this was just another way to ensure that important events were given due attention and would not be forgotten. Hence commemorative mugs bearing the words ‘The Unfortunate London’ were produced, and photographs of survivors were sold, as well as books that used the wreck to preach about morality.

A notable survivor was seaman John King – often portrayed as the hero of events for helping to ensure that a few people survived. He became famous and people wanted to buy photographs of him and to get his autograph.

1866 was a very different world to today, and it does seem a long time ago – over 150 years in fact. But despite the differences, we shouldn’t forget that those who lost family and friends on the SS London still grieved, and as one husband wrote on hearing the news of his wife’s death: ‘Surely no heavier affliction ever fell on a man than this…’

Simon Wills is a maritime genealogist and history journalist. His heavily illustrated book is The Wreck of the SS London (Amberley 2016).

Simon Wills is a maritime genealogist and history journalist. His heavily illustrated book is The Wreck of the SS London (Amberley 2016).

Prompted by his purchase from an antique shop of a cartes de visite from the 1860s, picturing three survivors, Family Tree contributor Simon Wills set about researching the London’s story in depth. Some ten years on, the result is this thoroughly detailed book, published 150 years after the disaster, in which readers are transported back to ‘the dangerous world of Victorian ships’, when vessels of the British Empire traversed the world’s seas, with scant regard to safety by shipowners, which in turn was ignored by officialdom.

By unearthing records relating to the disaster from around the globe, including the crew and passenger list from Canada’s Maritime History Archive, Simon weaves together a comprehensive history of the London, the tragedy, the aftermath and many of the people involved in its long-forgotten story.

(Images copyright Simon Wills)

.jpg)