Find out how passenger lists can help you find ancestors who travelled to the UK from overseas, or left Britain for a new life in another country. This guide will help you trace your ancestors on the move.

Passenger lists can be an invaluable source for researching emigration and immigration. If you can’t find someone on the census, passenger lists may be worth a look, in case they were in fact living overseas.

Passenger lists guide: quick links

- A background to British passenger lists

- Which details do passenger lists contain?

- Additional details on later passenger lists

- Problems with passenger list records

- Tracing both 'ends' of your ancestor's journey

- How to find passenger lists

- Why might your ancestor have moved countries?

- Passenger lists in 3 easy steps

- Expert advice: How a passenger ship manifest can help you

- Claim your FREE 1921 Census Resource Kit when you sign up to the Family Tree newsletter

A background to British passenger lists

It’s an inescapable consequence of living in an island nation that, prior to the advent of air travel, everyone arriving in – or departing from – the country would have done so by sea.

Over the centuries, some efforts were made by the authorities to keep records of those arriving on these shores (there was less interest in those heading in the opposite direction) but it wasn’t until the last few decades of the 19th century that the British government began to maintain anything approaching a comprehensive record of arrivals and departures; even then, the records didn’t cover voyages within Europe.

The National Archives holds a variety of records relating to ‘alien’ arrivals in the UK from Napoleonic times onwards, but these certificates and passenger lists are far from being comprehensive. There are also good collections of records relating to naturalisation and citizenship for people settling in the UK who wished to become naturalised/a citizen, but it’s certainly the case that attempting to find details of people arriving in the UK before 1890 is a bit of a hit-and-miss affair.

In this guide we are going to concentrate on passenger lists (also called passenger manifests) - both the records that will help you track down people arriving on British and Irish shores, and those leaving them - travelling or emigrating overseas. We'll also look at some records to help you locate ancestors' overseas inbound details too.

What details do passenger lists contain?

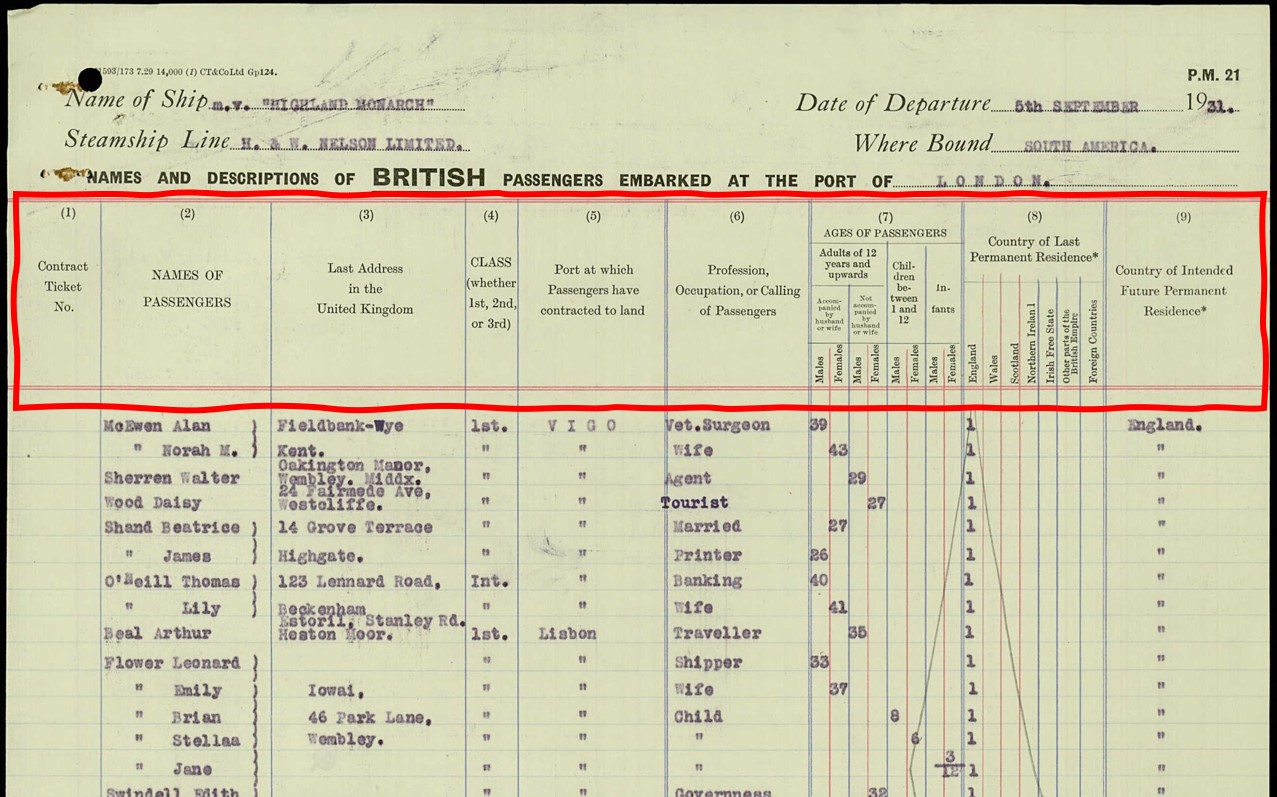

The details to be recorded were set out in the passenger list legislation and varied over the years.

By 1890, the lists (both outgoing and incoming) were recording the names and ages of the passengers together with their:

- Occupation: ‘Profession, Occupation or Calling’

- Nationality: There were separate columns for ‘English’, ‘Scotch’, ‘Irish’ and ‘Foreigners’

- Ports or departure & arrival: The lists also recorded the ports of embarkation and landing for each passenger along with details of the ship and of the voyage itself.

- The records also include some non-standard lists, usually those for smaller vessels, many of which record no more than the names of the passengers.

Note: The passenger list legislation covered not only passenger ships (defined as ships carrying more than 30 passengers) but also merchant vessels that carried smaller numbers of passengers alongside their usual cargo.

While the earlier passenger lists were handwritten, later ones were typed. Be sure to examine the column headings for every passenger list you obtain for your ancestors. The details recorded do have variation - and do often contain fascinating and useful nuggets of information. Image used with permission of Findmypast.

Additional details on later passenger lists

The 1920s and ’30s were a golden age in the history of ocean travel, with thousands of people travelling by ship each year to destinations in all parts of the world. For a certain class of people, travelling back and forth across the Atlantic became almost a way of life. And from a family history perspective, the post-World War I records are even more valuable.

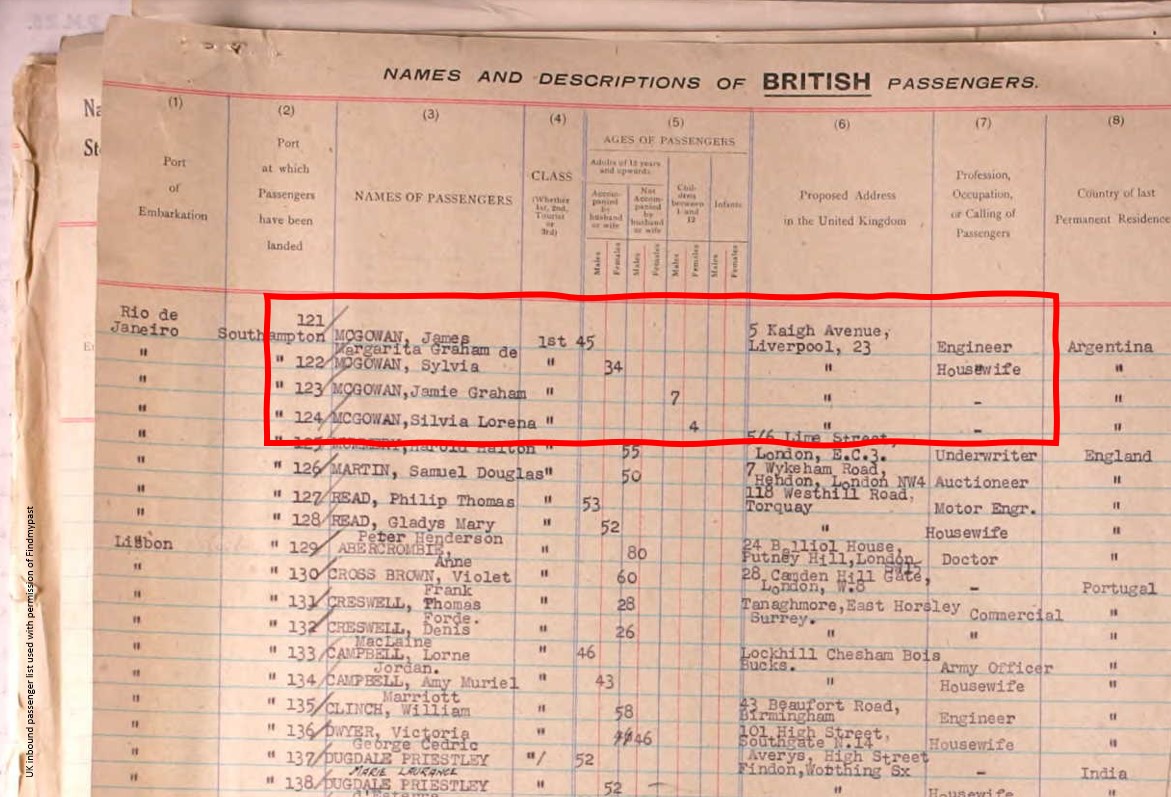

Outward lists begin to record the passengers’ ‘Last Address in the United Kingdom’ and those for incoming passengers record their ‘Proposed Address’.

Although relationships aren’t given, with the passengers’ names and ages, listed together in family groups.

On the image above, the four entries for people named McGowan look very much like a family. While relationships to one another aren't recorded on passenger lists, the other details enable us to see possibilities, which we can verify using other records such as census, birth and marriage records. Image used with permission of Findmypast.

We can almost use the lists as 'mini census' returns, providing us with a snapshot of the family at times when we might otherwise not have a very clear picture of them. This is particularly important when we consider the loss of the 1931 Census returns for England and Wales (though that for Scotland survives and is due to be released after the 100 year closure period elapses). If you’re lucky enough to discover a family on a passenger list around this time you’ll find that you have the perfect census substitute.

Most of the post-World War Two lists are typewritten rather than handwritten, making it easier for us to read the details and, perhaps more importantly, making it easier for the people who were employed in transcribing the records to read the details.

From 1955 the lists become even more useful as, instead of their ages, we now get the exact dates of birth of the passengers, both on the incoming and the outgoing lists. Knowing someone’s birthdate is an excellent way of working out whether you’re researching the right person or not.

In addition to the details recorded about the individual passengers, the lists also tell us a great deal about the voyage and about the ships themselves. There’s a wealth of opportunity for further research here.

Problems with passenger list records

On the downside, as with just about every set of records we use in our research, the standard of the record keeping varies greatly.

- The quality of the handwriting is often an issue;

- as is the frustrating habit that the clerks had of abbreviating the passengers’ first names, sometimes using just initials.

- Even more exasperating is the all-too-common practice of entering married women simply as, for example, ‘Mrs. Smith’.

Tracing both 'ends' of your ancestor's journey

Do remember, that there’s another way to get into the records and it’s based on an important principle: all journeys have two ends.

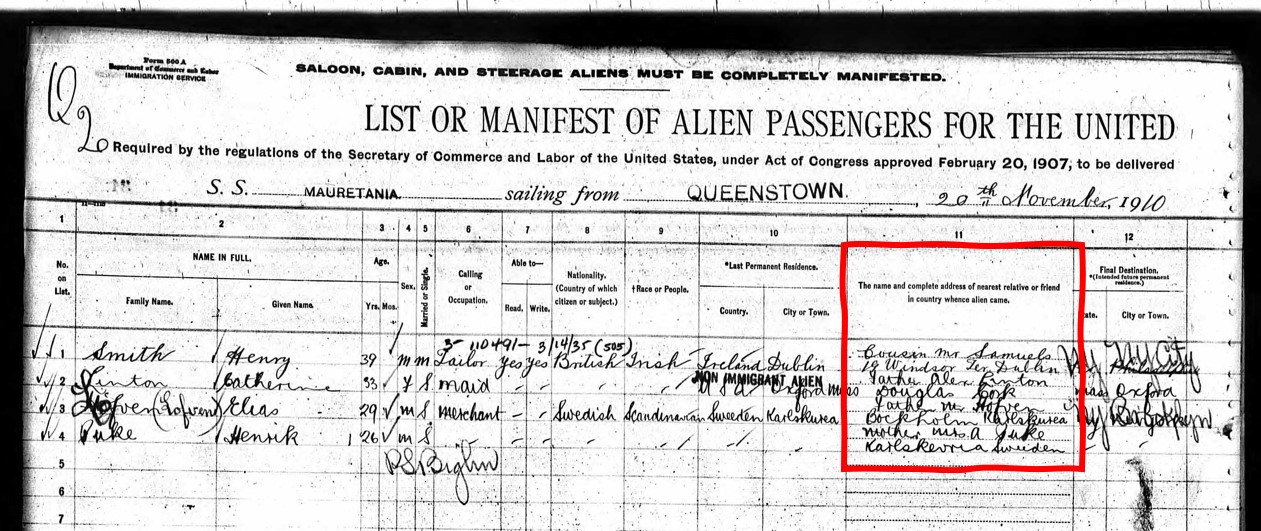

If your ancestor sailed from Southampton to New York, you should find a record of their departure in the UK passenger lists, but there’s also a good chance that you’ll find something at the other end of the journey, in the US records.

Ancestry, Findmypast, MyHeritage and FamilySearch all have excellent collections of passenger lists and other associated immigration and emigration records that might add considerably to the story. There are lists covering the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries to which our ancestors might have travelled.

Be sure to obtain all possible details related to your person of interest from the passenger list. Here we see US inbound alien arrivals. Each of the people travelling do not look to be travelling with family members. The column on the far right-hand side, however, names a relative and location for each, making for easier confirmation as to whether or not the record is for your ancestor.

How to find passenger lists

UK outbound passenger lists

- Of the original records that are kept in BT 27 at The National Archives, Kew, passenger lists for those leaving UK shores survive between 1890 and 1960. They may be viewed online (£) at Ancestry and Findmypast

- The Scottish Emigration Database (free) contains transcripts of records of more than 21,000 passengers who embarked at Glasgow and Greenock for non-European ports between 1 January and 30 April 1923, and at other Scottish ports between 1890 and 1960.

- ScotlandsPeople has a digital archive of Highlands and Islands passenger lists, 1852-1857, which can be searched free.

UK inbound passenger lists

Of the original records are kept in BT 26 at The National Archives, Kew, passenger lists for those arriving on UK shores survive from 1878 (largely from 1890) to 1960. They may be viewed online (£) at Ancestry.

About the period 1878-1890: A handful of inbound passenger lists survive before 1890. These include one isolated survival from 1878, some for the years 1883 to 1887. And all but one of these early UK inbound lists relate to ships arriving at the Irish port of Queenstown (Cobh), the one exception being for the RMS City of Rome, which arrived in Liverpool in October 1885.

European lists not included

It should be noted that these UK outbound and inbound passenger list collections mentioned above do not cover voyages that began or ended at ports in Europe or the Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, from 1890 until 1960, coverage of incoming and outgoing passenger lists for journeys beginning or ending in other parts of the world is as comprehensive as any set of records like this can be expected to be.

Finding passenger lists around the world

Passenger lists created overseas may be found in other archives around the world.

Use Cyndis List of useful family history websites, looking in the category 'Ships and Passenger Lists'. Learning about the vessel your ancestors sailed in is an interesting avenue to explore.

Web directories: Try browsing Cyndi’s List for links on ships and passenger lists.

Libraries & archives: You could also try contacting the major libraries and archives in the country where your ancestor travelled to or from, as they may well hold original records.

America’s official immigration centres 1820-1954 are Castle Garden and Ellis Island.

Nearly a million people passed through the immigration station at Pier 21 in Nova Scotia in the 20th century. Image by Skeezix1000 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11101808

Canada's Pier 21, the Canadian Museum of Immigration, is located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and was in operation 1928-1971.

National Archives of Australia research guides will point you in the right direction. Passenger lists 1924 onwards are held by NAA; pre-1924 research via your state of interest.

New Zealand Archives' immigration research guide explains that inbound passenger lists 1839-1973 are available via FamilySearch.

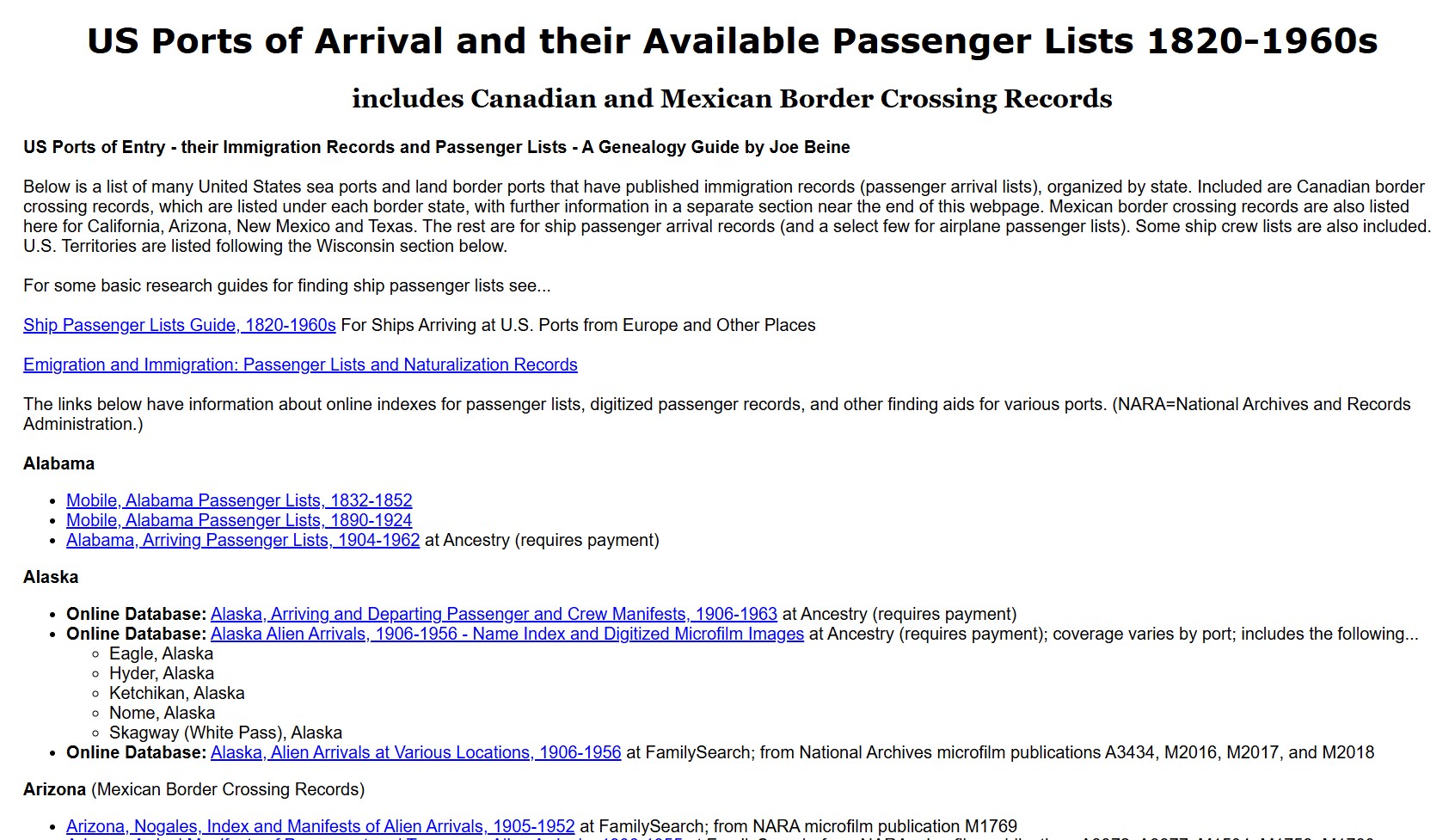

Joe Beine's Gene Search website is a treasure trove of shipping and passenger related information, including emigrants from Europe.

Border crossing records: To trace ancestors who may have arrived at a different port, or who crossed the border from Canada or Mexico, try Joe Beine’s guide at Gene Search, which details US ports of arrival and their available passenger lists 1820-1957 and includes Canadian and Mexican border crossing records.

NARA: The National Archives of America has plenty of useful immigration information.

Ancestry's Immigration & Travel collections: This has a number of overseas immigration records in its ‘Immigration and Travel’ category, such as passenger arrival records for Canada, North America and Australia, but you are likely to need a worldwide subscription to view them.

Findmypast's Transatlantic Migration Index: This contains the names of over 40,000 individuals who travelled from North America to Great Britain and Ireland between 1858 and 1870. See also Findmypast's Travel & Migration collections for further records of interest for ancestors' travels.

Alien Arrivals

Explore records of ‘aliens’ at Ancestry.co.uk, using England, Alien Arrivals 1810-1811 and 1826-1869, indexed with digitised images. These include the Aliens Entry Books 1794-1921, which feature Home Office correspondence about aliens, indexes to aliens’ certificates 1836-1852 and applications for naturalisation.

The retired 'Moving Here' website had images of alien certificates issued at the port of Hull 1793-1815. Access an archived version of the site.

Transported convicts

Between 1787 and 1868 more than 160,000 people were transported to Australia. Search records of transportees to Australia, 1787-1879, (including HO10, HO11 and CO209/7) on Ancestry (worldwide subscription required to view records);

At Findmypast search the Australia Convicts Ships database 1786-1849;

And search the Ireland to Australia Transportation Database at The National Archives of Ireland.

Naturalization & Denization

- You can search 300,000 naturalisation records at The National Archives, including Naturalisation case papers, 1789-1934 and 1934-c1968 (not all records survive).

- TheGenealogist provides access to details for 150,000 people's Home Office records of naturalisation and denisation spanning 1609-1960. As well as providing the date an ancestor may have received British naturalisation or denization, other details may include a change of name when they arrived in the UK.

Why might your ancestor have moved countries?

Above we have looked largely at the key record collections that will help to trace ancestors who left or arrived on UK shores, and also at possible collections to help trace ancestors travelling to/immigrating to other countries, such as the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. These records covered above tend to span the mid-18th century onwards.

There are of course many reasons why people may have moved, and it is extremely valuable to learn about this historical context so as to more fully understand their motivations or circumstances. From indentured servants from the 17th century, to enslaved ancestors, those seeking freedom from religious persecution, those transported for their crimes, Gold Rush adventurers and Ten Pound Poms, there are numerous reasons why you may find someone on the move. So when you find them in the records, spend the time to learn about the location and line of work they left behind and the place they ended up too, to help enrich your family story. (Remember too that they may have worked on vessels, so crew lists are well worth tracking down as well).

Passenger lists in 3 easy steps

- Check the BT 26 inwards passenger lists for ancestors who travelled to the UK, and explore the BT 27 outwards passenger lists for ancestors who may have emigrated.

- Consult overseas archives to trace ancestors who travelled to or from another country.

- To find out what information you may be able to find within the records, be sure to read the ‘About’ section for each collection.

Expert advice: How a passenger ship manifest can help you

Find out how a passenger ship manifest can help you trace your immigrant ancestors, in this expert guide from Catherine A. Daly, director at the American Family Immigration History Center.

There are a variety of things a person can learn about their relatives from reading a passenger ship manifest.

- Changes of name: An immigrant’s given name and surname used in their country of origin, which can be quite different from the names we knew them by.

- Extended family clues: The column detailing the name and address of the person the immigrant is joining in America may lead to an expanded discovery of family.

- Ancestral origin clues: The immigrant’s last place of residence (town & country) can lead to an opportunity for further online research in that town or country’s archival records—or become a new vacation destination to retrace your relative’s journey!

Understanding a passenger ship manifest

There are other things on a manifest that occasionally appear that aren’t so commonly understood:

What if your relative’s name is crossed out?

- That might mean they upgraded their class of ticket. Their original listing was crossed off, and they were added to the page for the upgraded passenger class. You will find their name listed twice on the ship manifest.

- It might also mean, however, that your relative did not board the ship. They might have missed it or changed their plans, or fell ill and health officials prevented them from boarding. You might see notations in the left hand column next to their name as "N.O.B." (Not On Board), "did not sail," or "Not Shipped." If that’s the case, continue searching for your relative’s immigration record because you haven’t yet found it!

The children of 'alien passengers'

It’s possible to find your relatives on the “List of Alien Passenger” manifest page, but you notice notations written next to their children:

- USB or US Born: That indicates the parents were foreign-born but their children were born in America. Children of US birth were not inspected in the same manner as non-citizens upon returning to America. This can also reveal that a relative you had assumed was European-born and an immigrant was actually born in America into an immigrant family.

- Claims USB or Claims US Born: This often indicated children born in the U.S. who had been taken back by their parents to the parents’ country as small children. As young people, they returned to the United States, but unfortunately, their parents had never obtained proper documentation of their earlier birth in America.

Non-immigrants on the manifest

- Transits / In Transit: You may have wondered why some people are marked as non-immigrants, yet they are not U.S. Citizens. Usually, this indicated that this was not the first time this person entered the United States. There were travellers who did not plan to stay in America who were marked “Transits” or “In Transit.” They may have been on their way to someplace else, were only visiting, or were students who planned to return home. This was heavily seen with people passing through the Port of NY going on to Canada.

It’s worth mentioning an idiosyncrasy on the manifests that is specific to the British Isles. Although the people of Wales, England, Ireland and Scotland favored the use on a middle name or middle initial, as a rule, the ship pursers didn’t include those on the manifests when they were written.

Find out more about the American Family Immigration History Center's records

Explore thousands of immigration records at the American Family Immigration History Center on Ellis Island, New York, and online via the Center’s website. There are more than 51 million records, including passenger records, ship information and original manifests.

The Community Archive is a growing collection of annotations to the passenger records. Members of The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation create the annotations, which give new information on a passenger's background and life in the United States. Non-members and members alike can view the annotations. Find out more on the website.

Note: In our guide we are referring to these records as the UK passenger lists as that is the way in which you will frequently see them named. The names of the constituent countries has changed over time: the Act of Union (effective from 1 January 1801) formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The 1920s saw Irish self-goverance introduced and the name was changed to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 'Southern Ireland' was named the Irish Free State, becoming the Republic of Ireland in 1949.

Claim your FREE 1921 Census resource kit

Get family history advice direct to your inbox with the Family Tree Newsletter.

Sign up now and claim your free 1921 Census resource kit!

As a thank you for signing up to the newsletter we'll email you a downloadable resource kit giving you all you need to make the most of the 1921 Census and find out more about your 1920s ancestors.

Originally published February 2015. Reviewed 11 February 2026.