28 January 2022

|

In the March 2022 issue of Family Tree, Steve Roberts explores the rulers of the House of Wessex, and in his complementary blog below he takes a light-hearted look at further snippets from this fascinating chapter of history.

I’m heading back to the so-called Dark Ages for this light-hearted blog, which will accompany a more serious tome published within the pages of Family Tree magazine. I’m pondering the House of Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England, and ultimately the ‘first among equals’, which saw it forge a nation of ‘England’. I’ve decided to arrow in on Alfred the Great, the most famous of all the kings of Wessex, he of dust ups with Danes, burned cakes and the ability to be an autodidact (that’s because he was self-taught at Latin, which puts a lot of modern Brits to shame).

Wantage

I’ve started my journey in Wantage, the birthplace of Alfred possibly in 849 AD. Wantage has moved about like a Danish horde. It was in Berkshire but occupies a spot in Oxfordshire these days. My own town has done the same, of which more later. Alfred has an imposing statue in the Market Place which was unveiled a Millennium after the king sat on the throne (871-899). It was sculpted by Count Gleichen (1833-91), or to give him his full name, Admiral Prince Victor Ferdinand Franz Eugen Gustaf Adolf Constantin Friedrich of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, a relative of Queen Victoria, who was noted to be a toastmaster’s worst nightmare. It is impressive just like the sculptor’s long-winded nomenclature.

Known as ‘Wanating’ in Alfred’s day, Wantage got a mention in Domesday Book and once had its own little railway, the ‘Wantage Tramway’, but that closed to passengers a long time ago in 1925. Maybe they didn’t realise that people would be flocking in to see Alfred’s statue. The town isn’t just famous for Alfred coming into the world here at the royal palace. It was also the place where one of the children of the US retail entrepreneur, ‘Mr Selfridge’, went to school. That would be the youngest daughter Beatrice. I digress. There’s a plaque on the statue which tells me of Alfred’s many achievements: ‘The land ravaged by a fearful enemy, from which he delivered it’; ‘Alfred found learning dead, and he restored it’. This is why he’s the only one of our monarchs suffixed ‘The Great’. His achievements would be mutually exclusive in mere mortals. You can either fight the Danes or teach yourself Latin but surely not both. Alfred did both and more besides. The statue was unveiled by the Prince and Princess of Wales on 14th July 1877. So, this would be ‘Bertie’, the future Edward VII, who’s not known as ‘The Great’ because he made a career out of frivolity and womanising and little else. He may not have been the best person to unveil a statue of Alfred but at least he was royal.

I like a plaque or information board and found one or two about the place. There was one telling me of an outbreak of ‘Asiatic Cholera’ in the town in September and October 1832 and the fact that 16 victims had been buried ‘between the wall (where the board had been erected) and the pathway’, with another three also being carried away who were presumably buried elsewhere. According to the board (restored 1960) it was the intervention of ‘Him’ that brought these unwelcome events to a close when he had a word with the ‘Angel of the Pestilence’, pointing out that enough was enough. In the time of our most recent pandemic I felt a tad uncomfortable and wondered whether I should pray more. I then discovered a blue plaque telling me that the old town hall (1877) had been built on the site of the Falcon Inn, which I found regrettable; another pub closure. It was time to move on.

Athelney

When Alfred acceded to the throne in 871 the wars with the Danes were in full flow. In fact, Alfred and his elder brother (and king at the time), Ethelred I, had fought and won the great battle at Ashdown (most likely in Berkshire) which stopped Wessex from being completely overrun by the pagan host. That Ethelred by the way should not be confused with another later Ethelred, the Unready, who I’ll therefore say nothing further about (for now). Ethelred I was busily praying in his tent when Ashdown got underway, leaving his kid brother to do the hard work. Alfred was certainly not short of courage or dynamism. While the king procrastinated Alfred got busy with his axe (his Wantage statue has just such an axe although his other hand holds a scroll: the martial king meets learning again).

That year of Ashdown (871) was a tumultuous one. The West Saxons (or the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Wessex) and the Danes fought one another to a standstill with more dust ups than you get in the modern town centre on a Friday or Saturday night (even without the Falcon to provide a drunken army’s liquid sustenance). Ashdown was the standout battle of them all. Ethelred would die a few months later and Alfred would be in the hot seat and a hot seat it was. There was a period of relative calm though until 878 when Alfred experienced both his ‘darkest hour’ and his ‘finest hour’ as we get a bit Churchillian.

The Danes came looking for bother again, led by one Guthrum. Alfred, caught on the hop, had to seek refuge in the Somerset Levels, specifically the Isle of Athelney where he built some sort of fort and plotted his comeback. It was at this moment of his lowest ebb when he allegedly burned the cakes, a surely apocryphal tale of a king laid low, so low that he sought refuge in a humble cottager’s, took his eye off the prize and had so many incinerated cookies on his hands. We presume that he was so beset by his problems that his concentration levels were shot. He was presumably well harangued by the lady of the cottage who was no doubt rolling her sleeves up and looking around for a rolling pin to belt him with. I don’t believe there was any of that ‘Don’t you realise who I am?’ nonsense from Alfred, who took his admonishment on the royal chin.

Monuments to Alfred abound. At Athelney there’s a Grade II Listed memorial (1801) marking the spot where we presume that he had his fortress and where later he built an abbey in thanks for his victory (read on). Just six miles or so away is North Petherton where they discovered the ‘Alfred Jewel’ in 1693, an elaborate late-9th century ornament which we presume Alfred held in his hand. It looks like the kind of thing a king would have owned. Perhaps he had it on him as he plotted his redemption.

Edington

It was no easy matter to get word out to your followers in 878 AD. In the days before the Internet and pesky social media you had to rely on messengers and word of mouth. It’s not like today when your scribe makes a Twitter utterance and his vast army of followers (638 at the last count) immediately stop whatever they’re doing to pay attention. Anyway, however he did it, Alfred did it. He got word out to his loyal subjects that he was still about and keen to get his royal backside back on his throne. They were no doubt commanded to assemble for their king who would lead them to a glorious victory over the Danes whose reputation in Wessex was akin to a social media troller or financial scammer. Alfred’s great comeback was on.

The battle was fought at Edington (or Ethandun). Why have just the one name when you can have at least two? I’m sure the naval prince would have concurred. This is arguably one of the great moments of English history when Alfred and his merry men swarmed out of the Levels and descended on the Danes whose turn it was to be caught with their Scandinavian pants down. Edington was one of the most decisive battles in our history, one that determined that Wessex would survive and have the opportunity to morph into England, relegating the Danes to a bit part in our subsequent story, although to be fair they did have a trio of kings in the 11th century, including that apparent berk Cnut, or Canute, whose been much mocked for allegedly trying to turn back the waves. I say ‘apparent’ because the smart money seems to have been on him pulling off this stunt in order to show his camp followers that even a king had limitations on his power. Why he’d want to do that though I’m not quite sure. Guthrum the Dane meanwhile had to swallow his pagan pride and be baptised a Christian.

Christchurch

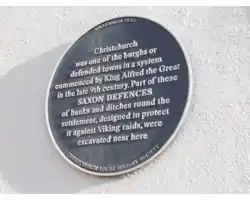

So, Alfred had secured his throne and the future, which was to an Anglo-Saxon England, well, until ‘1066 And All That’ at any rate. Alfred now needed to consolidate his gains and one method he employed was the burh, or fortified town (we get our modern word ‘borough’ from this). The idea was to have safe havens into which folk could retreat in the event of further Danish incursions. They were dotted about such that no-one was hopefully too far away from one of these sanctuaries. So long as you could move quicker than the Danes you’d be o.k.

My home town of Christchurch is one (Dorset, but once of Hampshire). We tend to regard our place as having been established by Alfred, around 890. We have Anglo-Saxon bits, including a water mill (mentioned in Domesday Book), remains of the walls (commemorated with a blue plaque) and displays in the local museum (including a grave mock-up as an Anglo-Saxon cemetery was discovered under a supermarket car park). That was a bit like Richard III being found under his car park in Leicester. I often wonder whether any of the shoppers ever realise they’re pushing their trolleys over hallowed ground. Probably not.

Wareham

If you want to experience what an Anglo-Saxon burh has to offer then head for Wareham, which is indisputably Dorset, and always has been. The Anglo-Saxon walls, humungous earthen banks, are still massively impressive, and you can walk atop them. O.k. they don’t quite form a full circuit these days but they’re not that far short. It’s a bit like walking the walls in York or Chester but without the masonry. Wareham doesn’t just have its walls, it also illustrates Anglo-Saxon town planning rather well with its North Street, South Street, East Street and West Street. You get the idea. Wareham was significant in Anglo-Saxon times being a royal burial place, one of the internments being of Edward the Martyr, a later king, who died in 978, his moniker ‘The Martyr’ telling us that he came to a sticky end. He was murdered just down the road at nearby Corfe, allegedly on the orders of his naughty stepmother, who wanted her own son on the throne (that Ethelred the Unready again). Edward’s remains were later removed from Wareham.

I’m done: admire Alfred’s statue (Wantage), experience his great comeback (Athelney and Edington) and ponder his town planning (Christchurch and Wareham).

Read Steve's House of Wessex article in March Family Tree.

Blog pictures all copyright Steve Roberts.