26 August 2016

|

Barnardo’s releases details of unseen Victorian archive records

Barnardo’s has today released details of unseen Victorian archive records that reveal what life was like for the first fostered children, when the scheme was originally pioneered in England by the children’s charity in 1887.

Find out more about the boarding out scheme with this Q&A with the Barnardo’s charity.

Q: What inspired Thomas Barnardo to introduce foster care to England?

A: When foster care was first introduced to England in 1887, it was known as “boarding out”. Thomas Barnardo was inspired by a similar practice already taking place in the Scottish Highlands, Ireland and Scandinavia, where children who couldn’t live with their own parents were placed with families in the same village/town.

Many of the children cared for by Barnardo’s in the Victorian era lived in dirty overcrowded slums in the East End of London. Through the boarding out scheme, Thomas Barnardo hoped that the children would get to experience the fresh air, the countryside and life with a family.

Q: Who were the first foster children?

A: In 1887, Thomas Barnardo pioneered foster care in England, placing 320 boys in the home counties and East Anglia.

Many were from the slums of the East End of London, and had experienced abuse and neglect. Our archive records show that over a third of the first 456 boys to enter foster care had rickets, 21 had ringworm, and many had bad teeth.

Children who were boarded out were termed 'orphans'. An orphan was a child with either one, or both parents dead, or parents who were unable to care for them.

Q: So, the first foster children were boys, when did girls join the scheme?

A: In 1889, two years after the boarding out scheme was established, our records show 124 girls in foster care, this was approximately a quarter of the children fostered that year. .

The girls chosen for the foster care scheme were those at risk of 'moral danger', or as we now call it child sexual exploitation.

Q: Who were the first foster carers?

A: Thomas Barnardo aimed to recruit foster carers living in rural areas across the South East and East Anglia as far away as possible from railway stations and factories in London. Our archive records show that we had registered foster carers living in West Suffolk, Surrey, Kent, Cambridgeshire and Essex.

Foster carers would often come from working, or “laboring class” backgrounds. They were paid a small fee, 5 shillings a week, to cover living expenses for the children in their care.

Thomas Barnardo was keen to recruit foster carers who were motivated for philanthropic reasons, and not for, as he wrote in one article “greed of gain”. This meant that the first foster carers could not rely on the children as their sole source of income.

Barnardo’s preferred the first foster carers not to have young children of their own, and they could not have any children boarded out to the workhouse.

Q: What would life have been like for the first foster children?

A: Our archive records reveal that the first foster children were generally well kept by their carers, enjoying the then luxury of a weekly bath.

As the children normally came from overcrowded conditions, Barnardo’s was keen to make sure they didn’t if possible sleep more than two to a double bed.

Barnardo’s visiting physician, doctor Jane Walker, wrote in her ledger, that many of the boys also got to eat cake, as it was their favourite food!

Q: How did Barnardo’s supervise the first foster children?

A: In each village which hosted fostered children, the vicar, and a local committee were responsible for the welfare of the children.

When the foster care scheme was established, Barnardo’s also employed a visiting female physician, Jane Walker, who visited the children every three months to check on their welfare and development.

Case studies of the first three boys to enter foster care

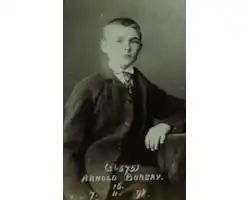

Arnold Thilibert Borsay

Born: 2 August 1882

Arnold made regular donations all his life to Barnardo’s in thanks for the 13 years of care he received, including seven years boarded out in the pretty hamlet of Eyke, on the Suffolk Coast.

He left Barnardo’s in 1898 to work at the Hotel Belgravia on the prestigious Victoria Street, London before migrating to British Columbia, Canada in 1902 under the assisted passage scheme.

Arnold was born in a beautiful, mountainous region of Switzerland to Julie, a kitchen maid. His father disowned him and deserted his mother. This may be why as an adult Arnold chose not to be known by his father’s name; Thilibert.

Arnold lived in Vaud, Switzerland not far from his mother where she could visit him. It’s unclear how Arnold came to be in London, but his mother signed the full agreement, handing him over to Barnardo’s in October 1885 when he was just three years old. Our records show that on entering Barnardo’s care, Arnold came down with chicken pox but soon recovered.

His entry record describes him as a 'most engaging little fellow … who prattles very prettily in a peculiar Swiss patois'.

In 1886 at the age of four Arnold was boarded out with Reverend and Mrs Darling. Arnold remained with them until 1893 and then moved in with the vicar’s gardener and wife Mr and Mrs Whyard and stayed with them for five years. Arnold would have been educated at Eyke’s village school, and would have had to behave according to its rules. A transcript of the school’s rules from 1857 is below.

Arnold died on 18 September 1963, generously leaving Barnardo’s $21,000 in his will which would be worth around £134,000 in real terms today.

Reverend Darling, vicar of Eyke, in the diocese of Norwich, came from a humble background in Northumberland. A wealthy patron, believed to be the Marquis of Waterford, who had Irish connections enabled Darling to study at Trinity College, Dublin. At the time wealthy patrons would sometimes pick out bright children and offer them the chance to receive an education. As a result, he wanted to help other children from humble origins.

Reverend Darling founded the village school, took in children from Dr Barnardo’s and built a special window in the church for children. According to Eyke village school records, where Rev. Darling and his wife Mary Emily (Milly) often taught lessons, the school role increased from 50 to 150 after the village welcomed 'local paupers' and children from Barnardo’s.

Rules of Eyke School: 1857 (set out by Rev. Darling)

This school will be opened on Monday the 14th day of June for boys and girls when the children will receive in addition to a sound scriptural education such other instruction as will fit them for their respective stations in life. Those who are distinguished for good conduct and ability will have an opportunity of becoming pupil teachers. A pupil teacher must be 13 years of age and receives from the Government £10 the first year which gradually increases to £20.

1. The payments will be 1d weekly or 1/- per quarter to be paid in advance

2. The School will be open from 9 till 12 in the morning and from 1 till 4 o’clock in the afternoon

3. No child can be admitted under three years of age

4. The children are required to be very clean and tidy and to have their heads well combed; their hands, face, neck and ears thoroughly washed every morning. Each child to bring a pocket handkerchief, and the girls must have pinafores

5. Children will be allowed to subscribe 1d a week to a clothing club, which will be established for their special benefit

6. Every Saturday will be a holiday. There will also be holidays at harvest time

Any infringement of these rules will subject the child to instant dismissal. It is particularly requested therefore that the parents make their best efforts to co-operate with the teacher in carrying them out, and that they will by their good example at home further the instruction which is given at the school.

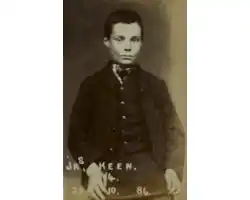

James Keen

Born: 18 May 1872

On arrival from High Wycombe at Barnardo’s in Stepney, 14-year-old James Keen weighed just 5 stones 6 lbs (35kgs) and stood at a diminutive 4’9’’.

James had a dilated heart which presents symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, fainting spells, palpitations, or chest pain and spent the first six months after admission in the infirmary.

James may have inherited his heart condition from his father, who had died of heart disease two years prior. His mother passed away when he was just six years old.

His grandmother, a housekeeper earning £12 per year, had taken James and his brother in after their father’s death. But at 62 years old her failing health meant she was no longer able to look after them.

She took the difficult step to trust James’ future to Barnardo’s, while his younger brother Harry stayed in High Wycombe in the care of a Mr Martin.

James had worked as an errand boy on a weekly wage of 3s. 6d but got into trouble for 'appropriating' some money off his employer. Lucky for James, he was not prosecuted.

Getting him away from the 'bad companions' who’d led him astray was one of the reasons Barnardo’s sent James to live with foster families for seven months. In 1887 he moved to Loughton in Essex where he could enjoy clean air, which may also have aided his health.

He returned to Stepney to undertake an apprenticeship for two years, leaving Barnardo’s care in September 1889 to take up employment.

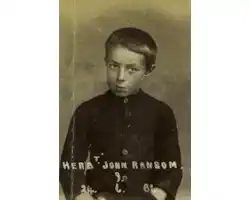

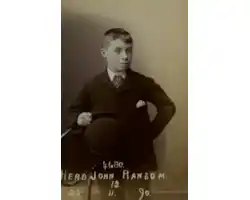

Herbert John Ransom

Born: 24 May 1877

When Herbert’s father died of dropsy (a condition where fluid accumulates in the body causing swelling) his mother, Ann, struggled to provide for her seven children. Her own poor health stopped her from taking on much work which left her with a meagre charwoman’s earnings of 7s per week and a parish supplementary allowance of six loaves and 6s per week.

Sadly this was not enough to care for all of her family so Ann made the heart-breaking decision to ask Barnardo’s to admit all four of her sons, while the three girls stayed home at Manor Park, London.

The Ransom boys’ entry record for Barnardo’s notes state 'the children have been decently brought up, and are described as bright, fairly intelligent, good tempered and obliging. They have attended day school, have had measles, and are in good health.'

Despite that, 9½-year-old Herbert spent three days in the infirmary in his first three weeks with Barnardo’s. his records show he was just 3’11’’ tall and weighed 48lbs (3 stone 6 lbs).

He boarded out for four months in the small town of Godmanchester, in what was then Huntingdonshire, before moving to a placement in Loughton, Essex for three years.

After nine months training back in Stepney, his time in Barnardo’s came to an end as he moved into employment in 1890.

Some 21 years later, the 1911 Census indicates Herbert’s own wife had passed away leaving him with two young sons living in West Ham, London.

Herbert was 83 years of age when he died in 1963.

Foster care today

Thomas Barnardo continued to develop the foster care scheme throughout his life, and by his death in 1905, 4,000 children were looked after in foster care. Today, three in four (75%) of children in care in England are fostered.

In 1887, Thomas Barnardo, who founded the scheme, wrote in Barnardo’s publication Night and Day: 'We are more and more disposed to believe that no system is better for the rearing of a certain class of our children than boarding them out (fostering) with respectable foster parents.'

Today, in its 150th year, Barnardo’s is appealing for more people to come forward to look after the 52,000 children who live in foster care in England, as well as those in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

To find out more about fostering, visit Barnardo’s at www.barnardos.org.uk/fostering, or call 0800 0277 280.

Barnardo’s Family History Service

If you have a deceased relative who was a Barnardo’s boy or girl, whether in the UK or as part of migrations to Australia or Canada, Barnardo’s could help you trace information about them and their life in Barnardo’s as part of its family history service – click here for more.

Archivist manager Martine King and her team assist with family history enquiries – watch our interview with her and discover more Barnardo’s facts here.

In Family Tree September Assistant Editor Karen Clare shared her experiences visiting Barnardo’s uniques archives and learned how a family historian maight trace a Barnardo’s child – get your copy of the issue here.