08 December 2016

|

Author Summer Strevens explains how she used family history sources, including parish records and local newspapers, to tell the story of Mary Bateman, who was executed in York in 1809.

Author Summer Strevens explains how she used family history sources, including parish records and local newspapers, to tell the story of Mary Bateman, who was executed in York in 1809.

On the morning of 20 March 1809, a Monday, the usual day designated for the execution of murderers, the woman who had earned herself the title of ‘The Yorkshire Witch’ was executed upon York’s ‘New Drop’ gallows, hung before a crowd variously estimated at between 5,000 to 20,000 people.

Yet when Mary Bateman was born, she was of so little importance that the date of her birth went unrecorded, as is so often the case with those who have risen to fame, and indeed notoriety, from humble origins. However, with some diligent digging, perseverance and above all the essential tool of ‘polite enquiry’, even when certain avenues of research prove factually inconclusive, correlation with different sources can help to establish a more complete picture.

The quest begins

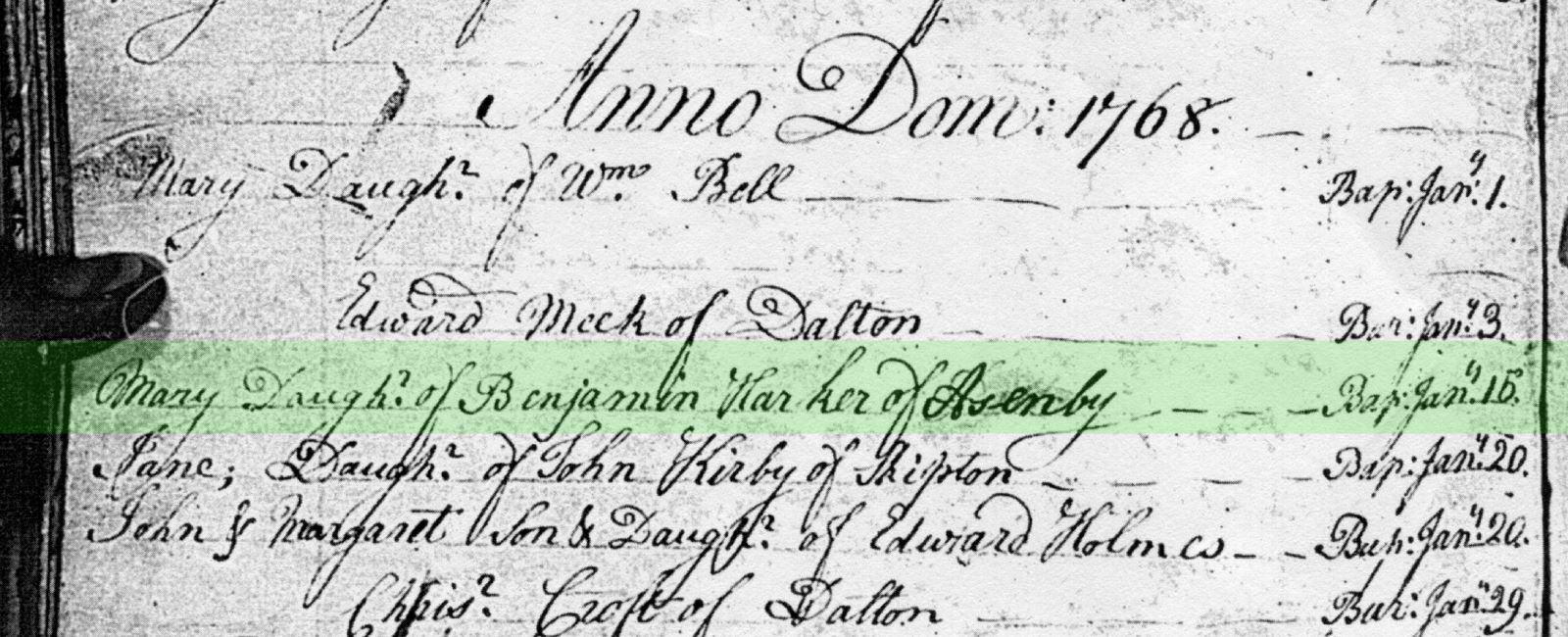

The third of six children born to Benjamin Harker and his wife Ann, née Dunning, who hailed from Brompton by Northallerton, Mary was noted as being aged 41 at the time of her execution, and while her exact birth date is not known, the parish records of St Columba’s Church, Topcliffe (pictured) in the North Riding of Yorkshire show her as being baptised on 15 January 1768.

The third of six children born to Benjamin Harker and his wife Ann, née Dunning, who hailed from Brompton by Northallerton, Mary was noted as being aged 41 at the time of her execution, and while her exact birth date is not known, the parish records of St Columba’s Church, Topcliffe (pictured) in the North Riding of Yorkshire show her as being baptised on 15 January 1768.

As a general rule, English parish registers recorded baptisms rather than births at this time, and as the average age at baptism had increased from one week old in the middle of the 17th century to one month by the middle of the 19th century, working backwards we can assume that Mary was born toward the close of 1767 or early 1768.

While of course parish records of births (or baptisms), marriages and deaths are an essential starting point when researching anyone’s life, not all registers remain in the hands of the church or parish to which they pertain, and Mary’s baptismal record (shown right) a perfect case in point, as I discovered after approaching the Rector of St Columba, who most helpfully pointed me in the direction of the North Yorkshire County Records Office, in whose care Topcliffe’s registers are now held. Yet even once a source has been tracked down, further frustrations can thwart one’s progress.

While of course parish records of births (or baptisms), marriages and deaths are an essential starting point when researching anyone’s life, not all registers remain in the hands of the church or parish to which they pertain, and Mary’s baptismal record (shown right) a perfect case in point, as I discovered after approaching the Rector of St Columba, who most helpfully pointed me in the direction of the North Yorkshire County Records Office, in whose care Topcliffe’s registers are now held. Yet even once a source has been tracked down, further frustrations can thwart one’s progress.

Though we are on firmer ground with regards to the details of Mary’s marriage - she was wedded to John Bateman at St Peter’s Church, Leeds on 26 February 1793 after what must have been a whirlwind romance of just 3 weeks (did she beguile her prospective husband with the same artifice she employed in exploiting the psychological weaknesses of her many victims?) definitively identifying the children born to the couple proved rather more problematical.

.jpg) While the excellent FamilySearch website (accessible and free!) proved invaluable in verifying St Peter’s parish records (today Leeds Minster - pictured), where the Bateman’s children were baptised, as the registers only give the father’s name and not those of the mother, as there were a number of ‘John Batemans’ in Leeds who chronologically ‘fitted the bill’ so to speak, again correlation with additional sources was called upon to name three of their offspring, with a further two possible siblings.

While the excellent FamilySearch website (accessible and free!) proved invaluable in verifying St Peter’s parish records (today Leeds Minster - pictured), where the Bateman’s children were baptised, as the registers only give the father’s name and not those of the mother, as there were a number of ‘John Batemans’ in Leeds who chronologically ‘fitted the bill’ so to speak, again correlation with additional sources was called upon to name three of their offspring, with a further two possible siblings.

We know that the Batemans had a son called Jack as mention was made of him at Mary’s trial, and presumably this child was the same John Bateman who was baptised on 21 February 1796 in St Peter’s, the paternal relationship noted as ‘Father: John Bateman’. The same records yield the earlier baptism of a Mary Bateman, again noted as daughter of John Bateman, on 16 February 1794, and a little less than a year after Mary and John’s marriage, so presumably she was the daughter that Mary referred to in a letter written to her husband from the condemned cell at York Castle Gaol, requesting that her wedding ring be bequeathed to the child, a traditional bequest as the girl, named for her mother, was the eldest.

The final days of the Yorkshire Witch

Records of Mary’s last days also indicate that she was allowed to have her youngest child with her in the condemned cell until her execution – although the sex wasn’t stipulated, this may have been James Bateman, again recorded as the son of John Bateman, who was baptised at St Peter’s on 19 July 1807.

However, the St Peter’s registers also hold entries for the baptisms of a Maria Bateman on 6 December 1801 and George Bateman on 20 May 1804, and as both dates fall neatly into the obstetric gap between the births of the eldest child, Mary, and James born in the summer of 1807, Maria and George may well have been the elder siblings of James who is the most likely candidate for the child sharing Mary’s imprisonment.

Mary’s genealogy certainly proved a fascinating aspect of the research for this book, and while the focus was directed on her immediate family, I do nevertheless wonder, how many of her descendants today still populate the Leeds area, and beyond, entirely unaware of their familial connections to their notorious ancestor, ‘The Yorkshire Witch’!

Summer Strevens is the author of The Yorkshire Witch, published by Pen & Sword Publishing. The book is the first since the publication chronicling her criminal career appeared in print in 1811, two years after her execution. Not only focusing on the details of her felonies and the consequences to her victims, it also examines the macabre legacy of her mortal remains, with the continuous public display of her skeleton in the Thackray Medical Museum until the recent removal of this controversial exhibit.

Summer Strevens is the author of The Yorkshire Witch, published by Pen & Sword Publishing. The book is the first since the publication chronicling her criminal career appeared in print in 1811, two years after her execution. Not only focusing on the details of her felonies and the consequences to her victims, it also examines the macabre legacy of her mortal remains, with the continuous public display of her skeleton in the Thackray Medical Museum until the recent removal of this controversial exhibit.

Find out more about using family history resources to solve genealogy problems in the January issue of Family Tree, available from our website.

Images: St Columba’s Topcliffe © Bill Henderson

.jpg)