04 October 2013

|

Sarah Lee sets out her case study of three names she researched as part of a wider project on the people remembered on the Great

Sarah Lee sets out her case study of three names she researched as part of a wider project on the people remembered on the Great War memorial in Carlisle Grammar School. Read Sarah’s story in Family Tree November 2013.

Case study 1: The deserter Beresford Karr Horan (1892-1915).

Beresford Karr Horan has one of the most surprising stories. He only attended the Grammar School for one term before moving on firstly to The Royal Naval College, Osborne, Isle of Wight, where his uncle, the Rev Frederick Seymour Horan, was chaplain and secondly to Marlborough College (1905-07). However in 1909, aged 17, he defied family tradition and migrated to Canada to farm; he was still in Ontario in 1911. Beresford is unusual amongst those on the memorial as he died before reaching Europe so he never entered the field of battle.

He was the elder son, born 14 Jan 1892 to the Rev Charles Trevor Horan and his wife Edith. Both families had an army and church tradition, which included service overseas, indeed the Rev Charles had been born in India and was Chaplain of All Saint’s Cairo when Beresford died. The Horan family also had a tradition of attending Cambridge University. Beresford’s family moved around with his father’s career. Beresford was born in Cambridge; he had one brother and one sister, and by the age of nine he was already away at boarding school in Norfolk.

He enlisted in the United States Marine Corps 14 June 1913, where he served for nearly two years, he was in the band, based mainly in California. In Feb 1915 he was listed as a deserter from the 4th Regiment the US Marines. We have been unable to find out why he deserted, however we do know that some soldiers deserted the American Army to join up elsewhere as they wished to fight and the USA did not enter WWI until 1917.

Within six months Beresford had joined the 30th Wellington Rifles as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF); he was given the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, however he was listed as a deserter on 17 Nov 1915, and died on Christmas Eve 1915. The Carlisle Memorial Register states that he ‘died from pneumonia following diphtheria contracted while training with the CEF’. However he was in disgrace as the Canadian Army refused him a war grave as he was a deserter.

Deserting two armies seems remarkable. He did have a magnificent gravestone where he was laid to rest in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, London, Ontario, Canada.

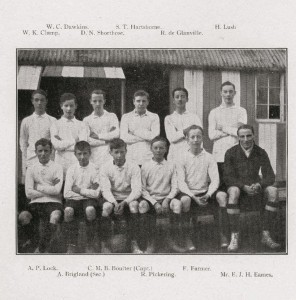

Robert de Glanville with rugby team, 1911.

Case study 2: Robert de Glanville (1896-1915) lied about his age when he enlisted.

Robert was born in Burma, son of an Irish father and Burmese mother; they had married in Burma in 1896. Robert was one of three children born to them. His father was a barrister who became President of the Burmese Legislative Council.

Robert was a real asset to the school as he was an excellent cricketer and he was in the rugby team too. He was a House Prefect and a keen member of the Debating Society, he opposed two motions one of which probably reflects his experience ‘that constant travelling narrows a man’s intellect’, he also opposed the motion ‘that modern warfare does not pay the victor’. His all round sports ability meant that he was awarded the Senior Challenge Cup in 1913.

After leaving Carlisle Grammar School Robert went to Glasgow University to study Engineering; however he was there for only a short time as he signed up for active service on 8 September 1914. Like many other recruits Robert lied about his age when he signed up to the 6th Battalion Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, adding two years to his age, saying he was 19 years and 11 months rather than his true age, 17 years and 11 months. He was 5’ 6 ½” tall and weighed 133lbs, with a dark complexion, dark hair and brown eyes.

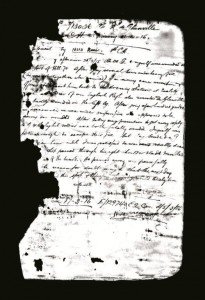

Robert died at Loos; unusually there is an account of his death written by a Private David D Munro, who lay beside him on the battlefield for the last hour of his life. He said that Robert died peacefully. The following day there was no trace of his body as there had been further shelling. He had been in France just 79 days.

It is good to note that Private Munro survived the war and was demobbed in 1919.

Private David D Munro's account of Robert de Glanville's death.

The Old Carliol (the school magazine) at first listed him as wounded, then as a POW before his death was finally confirmed. The following was in The Carliol in the spring edition of 1917.

From Private Norman Shaw, 3rd Cameron Highlanders: ‘Since I returned to this depot I have come into contact with numerous members of De Glanville’s old battalion…All speak well of him, and from what I hear his courage and pluck were splendid. These characteristics endeared him to his comrades, but not so much as another virtue of his – his unselfishness. Lance-Corporal Spence told me of how De Glanville often gave up his rations to any young boy in the trenches. That, I think, is a more meritorious deed than going out to help a wounded man. Again, I have heard of his perpetual desire to be doing something useful, and, as a result he was greatly in demand for listening posts, wiring parties and other tasks for which only volunteers are of use.’

Case study 3: Sarah Lee found herself warming towards one particular person, Robert Dixon Wills (1893–1917).

Robert Dixon Wills is my favourite; he was fairly easy to trace using the census returns and the records at TNA were tremendous at 26 pages long. Amongst other things they included his will, attestation papers and a copy of the letter sent to his family when they decided to exhume his body and rebury him in a bigger cemetery.

Robert Dixon Wills was the youngest of ten children born to Isaac and Jane Wills in the hamlet of Greenspot in the parish of Bowness-on-Solway. Isaac was the village blacksmith, like his father and grandfather before him. Two of Robert’s brothers, at least one cousin and uncle were also blacksmiths. Robert was the only one of the family to attend the grammar school. We presume he won a scholarship.

After leaving school Robert went to London and entered the Civil Service as a ‘boy clerk’ in 1909. War was declared in August 1914 and Robert volunteered on 1 September 1914, however he was not sent to France until 21 June 1916. As he enlisted in London he joined a London Regiment. He was 5ft 10” tall and wore glasses. He must have impressed those around him as he rose rapidly through the ranks and by the summer of 1916 he was a corporal. On 8 August 1916 Robert was part of a raiding party that was sent across no-man’s land to raid the German trenches and secure prisoners. The raid was not a success; although the wire had been broken by mortars, the trench itself was barricaded. Most of the party withdrew but Robert managed to crawl under the barricade, secure a prisoner and return with him. As they withdrew they were bombarded by mortars, his commanding officer Lt Read was wounded and had to take refuge in a shell hole with another wounded man. In his commanding officer’s report he says about Robert, ‘This man was very plucky throughout the whole raid and I should like to bring his name to your notice’.

Robert was awarded his military medal on 21 September, and sent to Cadet School for a commission in October; he was commissioned as an officer and posted to the 5th Border Regiment on 22 December 1916.

The Border Regiment was involved in heavy fighting at Wancourt on 23/24 April 1917; 74 men were killed or missing in action and 135 were wounded; Robert was one of the six officers who died. He was buried in a marked grave and after the war his body was exhumed and reburied in the Wancourt Military Cemetery.

There was still a Wills family living in the parish and I assumed that he would ‘belong’ to them; but after a discussion with them and some more research on the census it became clear that although both families had lived in the area for 200 or more years they weren’t connected. I advertised in the parish magazine as I thought that with nine siblings surely someone must know something. Eventually it was suggested by two different people that he might be connected to Margaret! After a brief conversation with Margaret we established that she was Robert’s great-niece, she had no knowledge of him and unfortunately there are no known photographs of him. I also located cousins in Canada who were equally amazed. There’s no trace of his military medal. It was sent to his widowed father, who was living with his married daughter Sarah Hannah Fitts. After Isaac died the Fitts family went to Poole where Samuel Fitts was appointed Harbour Master. Prior to WWI he had been Harbour Master in Rangoon. I’ve been unable to trace their children Edna, Beatrice and Thomas, which is a shame as I think they are the most likely people to have his medal.

- Anything to add? Email Sarah at [email protected].